What we might recognize as the English public school system began to take form, under Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, during the brief reign of Edward VI. It was thrown into chaos with Edward's death in July 6, 1553. The Catholic Chantry lands which were to be repurposed or liquidated to fund new schools in various localities remained the property of that church through the reign of Catholic Queen Mary I. Schools with powerful patrons with sufficiently deep pockets continued to educate students. Less well funded efforts managed as best they could if at all.

The administration of Elizabeth I was conspicuously filled with the great educators of the day. Roger Ascham, Thomas Smith, William Cecil, Nicholas Bacon, and other pedants, in communication with the great didact, Johannes Sturmius, in Strasbourg, Germany, were of the utmost influence in getting the concept of the public school back near the top of her agenda.

Cecil and Bacon, in particular, were early adherents of education for women. The effect of their advocacy was that many more women, in families with sufficient wealth, were exceptionally well educated through the finest tutors. Long practice, however, would keep schools male establishments for centuries to come.

Books were expensive at the time and difficult to come by. References to them sometimes require explanation. The better schools had excellent libraries, for example, donated by generous patrons, in which there was one copy of each work that was rarely if ever available to the students. The stacks were the domain of the head master. Each usher (lesser master) was directed which books to use for his classes.

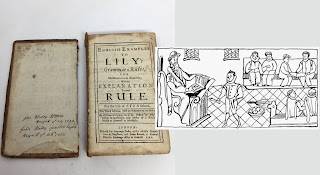

As for the students, at the better schools they might possess a catechism and a copy of Lilly's standard Latin Grammar. What they must certainly possess is clarified in the statutes of most schools, as here from the 1550 Statutes of the Free Grammar School of King Edward VI, at Bury St. Edmonds:

34. Ink, parchment, knife, pens, note books, let all have ready.1

They might also be responsible to provide their own writing surface.

35. When they have to write let them use their knees for a table.2

Books cost a lot of money. Desks cost a lot of money. In schools in humbler circumstances the students had no books at all — only their notebooks. The master dictated swatches of text to the students who copied the given swatches into their notebooks for lessons and exercises.

A list of books donated to St. Albans school library, between 1587-9, suggests how high the level of education might be at an elite school.

the whole workes of Plato, set out by Sarranus,... given by Mr. Francis Bacon.

Item, a fayre new Greke Dictionarie in quarto called Crispinus Lexicon,

A volume of Nizolius

Item, an ancient Greke Dictionarie in folio called Cornucopia or Keras Apod Oeias

A folio Pliny De Historia Naturali

A “faire newe Bible” of Tremellius with “Syriak Translation.”

Opus Aureum twoo excellent bookes of many ancient learned men’s sentences.

Cooper’s Latin Dictionary

a ‘Homer with enarrations of the best scoliasts,’

Demosthenes of the best and fayrest edition with scutcheons of the arms of my Lord Keeper

Again, humbler country schools, without wealthy patrons, could not hope to teach to nearly so high a level. Their much poorer head masters would arrive with little or no more than a basic library from out of which to dictate lessons. The school would have little or none at all to add.

The archives of one of the higher quality schools — the Merchant Tailors' school — have left behind a syllabus, compiled in 1607, for the six forms (what we call “grades”) that it taught. The following sample describes the afternoon lessons for the second form. It fills in a few more details.

The Afternoone.

1. They shall translate other dictata, or Englishes made out of the rules of verbs, wch have a nominative, genitive, or dative case after them, being uses of the examples.

2. They shall doe likewise out of the rest of the rules of the construction of verbs, and the other parts of speech that followe.

3. They shall translate a dialogue, being a dictatum, or English made out of Corderius his Dialogues.

4. They shall translate an epistle, being a dictatum, or English made out of Tully his Epistles.3

The morning was spent entirely upon grammar exercises from forms copied from dictation.

Corderius was another 16th century educator who wrote practice books for students. He and Tully were the entire reading of the students until the fourth form. The fifth form graduated to reading and imitating Latin and Greek verses. In the afternoon of the sixth form “The schoolemaister having opened, on the sodayne, the Greeke Testament, Esop's Fables, in Greeke, or some other very easie Greeke author, shall read some short sentence”. The class would spend the rest of the time doing various exercises on the sentence.

The Merchant-Taylor curriculum was the best among grammar schools in its time and it was well respected. But the pride of the free grammar school movement were the Foundation Schools. The very best were Refounded from the Catholic schools that had been disbanded under Henry VIII.

The schools thus refounded did the greater part of the education of England till the eighteenth century, and one of them, Westminster, developed into what was throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, admittedly the greatest of the public schools, taking the lead even of Winchester and Eton, alike in its numbers, its aristocratic connexion and its intellectual achievements.4

These schools were the equivalent of our modern Prep Schools. It is they that taught the powerful Latin and Greek curricula erroneously attributed to schools such as the humblest of grammar schools, at Stratford-upon-Avon, in order to explain the substantial classical knowledge of William Shaksper.

1The Victoria History of the County of Suffolk (1907). II.313.

2Ibid.

3Wilson, H. B. The History of the Merchant-Taylors School (1814). 163-4.

4Leach, Arthur Francis. The Schools of Medieval England (1916). 316.

Also at Virtual Grub Street and Tudor Topics:

- Were Back-Scratchers Really Invented in Elizabethan Times? August 20, 2023. “...when the domestic manners of the aristocracy, as well as others, were not of the most refined and delicate kind,...”

- Rocco Bonetti's Blackfriars Fencing School and Lord Hunsdon's Water Pipe. August 12, 2023. “... the tenement late in the tenure of John Lyllie gentleman & nowe in the tenure of the said Rocho Bonetti...”

- A Triple Wedding and Surprise Visit from the King (1536). July 31, 2023. “History was rushing onward at that point toward many fateful events”

- Ambassador Noailles’ Account of Mary I’s Procession to Westminster: September 30, 1553. September 17, 2022. “…in matching cloth of silver, was Lady Elizabeth, sister of her majesty…”

Queen Elizabeth’s Greatest Love, Robert Dudley, died on September 4, 1588. September 3, 2022. “Even after matters had settled down, Robert’s special treatment was the source of smoldering jealousy.”

- Check out the English Renaissance Article Index for many more articles and reviews about this fascinating time and about the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

- Check out the Queen Elizabeth I Biography Page for many other articles.

No comments:

Post a Comment