by Gilbert Wesley Purdy.

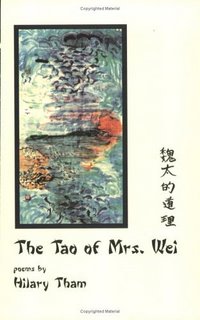

by Gilbert Wesley Purdy.The Tao of Mrs. Wei by Hilary Tham

Washington, D.C.: The Bunny and Crocodile Press, 2003

76 pp. $12.00 paper.

Chinese by descent and Jewish-American by marriage, Hilary Tham emigrated to the U.S., some thirty years ago, with a BA in English Literature from the University of Malaya. She has since settled in the greater Washington, D.C. area, published seven books of poetry and a memoir, received numerous grants, served as editor-in-chief of Word Works, Inc., and poetry editor for the Potomac Review. She paints professionally in the Sumi-e style. She is a regular presence at D.C. area workshops for children and the disadvantaged, open-mics, and poetry society events. Her most recent book -- The Tao of Mrs. Wei -- is published by The Bunny and Crocodile Press. Tham is a veritable poster-child for multiculturalism.

Like many other poets she goes looking, periodically, for something new to say in 50 poems, no more than two of which may be over 32 lines long. Such searches are necessarily undertaken poem by poem each appearing separately in small venues over a period of years. On this occasion, the search has resulted in The Tao of Mrs. Wei, the Mrs. Wei in question being an elderly Chinese matriarch created by Tham.

In the first poem of the collection, Mrs. Wei is at the cemetery unpacking a feast she has cooked for her dead father's ghost. Nearby is "An Englishman is visiting his mother's grave / with flowers.":

"When's your father coming out

to eat the food?" he asks.

Smiling, Mrs. Wei answers,

"Same time your mother

come to smell flowers."

The primary goal of The Tao of Mrs. Wei is to be entertaining and the poem is a strong start. Judged by that criterion, and by how well the persona is maintained, the first may be the most successful poem in the collection. Regardless, the criteria are generally met throughout.

The reader is likely to be entertained, in particular, by two traits that are persistent in the title character of this book. The first is her preoccupation with the Chinese spirit-world that accompanies her everywhere. The second is her utter lack of political correctness. The poet uses the persona to shield herself as she contrasts the strictures common to the contemporary poetry world with the straightforward freshness of her protagonist.

This provides the opportunity for any number of amusing, and refreshingly human, moments. At the end of "Mrs. Wei Meets the New Improved American Dream", for example, a fellow emigrant, from San Salvador, tells Mrs. Wei:

he is looking for a woman to marry,

any woman who can get him a green card.

"Better if she is blonde with big breasts," he adds,

holding out his hands to show the size

of his dreams, his hope green as an uncut tree.

While it might not be suggestible for Tham to write such a poem in the first person, her Mrs. Wei is at liberty to follow the conversation to its conclusion without appending an all too predictable withering rejoinder or commentary upon the damage done to the American psyche by the physiognomy of the Barbie Doll. The final seven words are entirely true to Mrs. Wei, and, therefore, entirely appropriate.

In Mrs. Wei's mouth, compliments to America and its way of life can be delivered without the least sense of opportunistic pandering or jingoism. For her, a trip to the grocery store is a wonder even if it is "Too bad American meat have no smell." She finds American drivers remarkably "polite". On the other hand, she can just as unaffectedly be "appalled" at how American cats live so much better than so many people in the world or allow the dissonant humanity of the unfettered desires around her to speak for themselves.

In the poem "Thirteen is Terrible, Mrs. Wei Said", Tham's protagonist reflects that each of her children became dangerously ill when they turned thirteen. The child Men Ya had mysteriously swollen up and the doctor's seemed unable to help him. Mrs. Wei's belief in spirits took her to a temple medium:

The medium said Third Grandaunt's ghost

wanted his soul to keep her company.

So I took a stone from her grave

saying "I reclaim what belongs

to me." Men Ya recovered

after he drank the soup I made

with that stone. I burnt a paper doll,

a boy, to keep Grandaunt happy.

"I believe Mrs. Wei sprang from an amalgamation of my mother and the mothers of my friends," writes Tham, in the author's note, at the end of the volume, and the authenticity of this remedy suggests that she sometimes takes her materials from them whole-cloth. More amusing is "Mrs. Wei the Gambler": a story about visiting the graveyard at night to plead for winning lottery numbers from the spirits and about the fate of poor Mr. Sung who paid dearly for acquiring his numbers in this fashion.

All of this said -- and even with Hilary Tham's unquestionable credentials -- there is something that borders upon the Charlie-Chan-ish in a handful of these poems. A handful of others seem clearly to be the thoughts of a highly acculturated Chinese-American emigrant. (In this regard, an exposition on the effects of homosexuality upon Ancient Greece and a grad-school joke -- amusing but entirely out of character -- come immediately to mind.) But, generally, the persona is well drawn and the poems are sprinkled throughout with the common situations of our lives and amusing observations such as Mrs. Wei is prone to make about them.

The poems in this collection were written over a number of years. Some have appeared in Ms. Tham's previous books and it is only recently that she has thought to collect them into their own volume. This (and an occasional self-indulgence) explains the strange discontinuities that sometimes run through Mrs. Wei's personality. On the other hand, Tham's love of the various Chinese matriarchs that have passed through her life explains so much in The Tao of Mrs. Wei that is delightful.

Gilbert Wesley Purdy's work in poetry, prose and translation has appeared in many journals, paper and electronic, including: Jacket Magazine (Australia); Poetry International (San Diego State University); The Georgia Review; Grand Street; The Pedestal Magazine; SLANT (University of Central Arkansas); Orbis (UK); Eclectica; and Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. His Hyperlinked Online Bibliography appears in the pages of The Catalyzer Journal. This review first appeared in The Danforth Review.

No comments:

Post a Comment